Emdad Rahman

On this side of the border, The Quality Street Gang may have a more notorious reputation – a band of criminals who operated in Manchester and who may or may not have locked horns with the Kray twins. However, I’m writing about a completely different gang, and one with far less dubious activities.

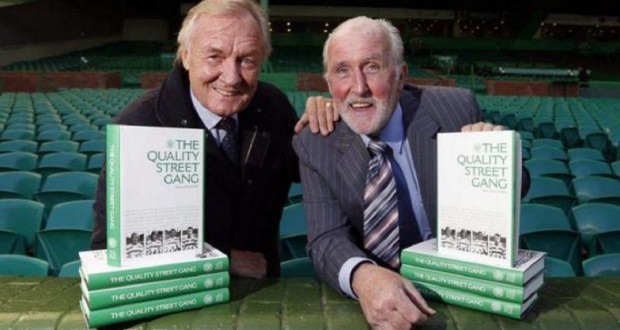

The Quality Street Gang, by Dunfermline-born, life-long Celtic fan Paul John Dykes, tells the tale of the greatest Celtic reserve team ever. It’s about how football visionary Jock Stein crafted two great teams in order to dominate the domestic and international game. Dykes writes about the shared experiences of these youngsters – how they developed from fledglings to football superstars both at home and abroad during a golden period for Celtic Football Club. The crop of youngsters were so talented that in the late ’60 s consideration was given to allowing the team to participate in the Scottish Second Division. This proposal was rebuffed by the powers that be.

You’ve won what is, arguably, club football’s greatest prize and you’re plotting your next move. You don’t have major financial clout or a Mr Moneybags owner. What do you do? You simultaneously develop a reserve team to seamlessly take over from the legends of old. That is the situation Jock Stein was faced with and solved to such great effect. After the triumph of Lisbon, Stein had a rebuilding programme in progress. The average age of the Lisbon Lions squad may have been 26, but Stein had already started to plan ahead – reassessing and rebuilding the greatest ever Celtic team.

It began with 19 year old reserve team captain David Cattanach, 21 year old inside forward Patrick McMahon, 18 year old Lou Macari and 20 year old Davie Hay. It was working. The conveyor belt was churning out the talent and it was clear that Stein had great faith in his fledglings. After all, the youth system at Parkhead had only produced the Lisbon Lions.

Fast forward to 1968, and the events leading up to an emphatic 6-2 League Cup win over Hibernian at Hampden gave further signs of Stein’s vision for the club. Before the final Stein handed three debuts in the second leg of the game against Hamilton Accies at Douglas Park: Bobby Wraith, John Gorman and a 17 year old named Kenneth Dalglish. The trio stepped into a team boasting an exemplary European record of one final, two semis and a last eight appearance in just six seasons. Stein’s quality assurance antenna was in full effect. His ethos was flawless. The youngsters would pass the standards test. They would break through into the first team, mingle and learn from senior pros who had done it at the very highest level. It was the football education a young player could only dream of experiencing.

[Adverts]

Part of Jock Stein’s masterplan and vision meant that the great man envisioned a lasting legacy. The Lisbon Lions may have made everlasting football history, but it was only a matter of time before they too would be replaced on the green fields. Not about to let his team follow the lead of Helenio Herrera’s “La Grande Inter”, Stein set about plotting and developing the future stars who would take up Billy McNeil’s mantle, grasp the baton from the wizard Jimmy Johnstone and step into the golden boots of the iconic Bobby Murdoch.

Celtic was the very first British club side to lift the European Cup. They had become to their opponents an internationally acclaimed name and a major scalp to beat. Teams both home and abroad raised their energy levels and their game when they played the Hoops. It was obvious to Stein, as a visionary, that he would need to nurture new talent – a new breed of stars to step effortlessly into those famous green and white shirts.

Stein set to work, nurturing a brilliant new reserve team in the late ’60s and early ’70s. They were labelled The Quality Street Gang, and several of that gifted breed – such as Kenny Dalglish, Davie Hay, Danny McGrain, Paul Wilson, Lou Macari and George Connelly – all stepped up, mixing with the old guard, winning silverware at Parkhead and representing Scotland on the international stage.

Stein set to work, nurturing a brilliant new reserve team in the late ’60s and early ’70s. They were labelled The Quality Street Gang, and several of that gifted breed – such as Kenny Dalglish, Davie Hay, Danny McGrain, Paul Wilson, Lou Macari and George Connelly – all stepped up, mixing with the old guard, winning silverware at Parkhead and representing Scotland on the international stage.

Those with football knowhow knew this sure progress wasn’t accidental. It was the summer of 1968, and Celtic Reserves needed a mammoth seven goal win against Partick Thistle Reserves to pip Rangers Reserves to the Reserve League Cup section. The Bhoys stunned the Maryhill Magyars with a 12-0 thrashing. Lou Macari was most prominent, with four goals. That year the Scotland national manager Bobby Brown made a request to Jock Stein for players for a warm up game. Stein duly sent his reserves, who outplayed the seniors – including Leeds United legend Billy Bremner – beating them out of sight with a 5-2 win. Two years later The Quality Street Gang lifted the Glasgow Cup, 3-1 against illustrious neighbours Glasgow Rangers.

By 1970-71 The Quality Street Kids were wreaking havoc as the highest goal scorers in Britain. Kenny Dalglish was mesmerising with 16 goals in a mere six games. With such glorious firepower the reserves wrapped up the League title, the League Cup and the Second XI Cup treble. Rivals Rangers were beaten three times out of hand in eight days of madness – the League and two-legged League Cup Final. The games weren’t even close: 7-1, 4-1 and 6-1. Kenny Dalglish may have plundered 43 goals in two campaigns but his exploits were overshadowed by Vic Davidson, 92, and Lou Macari, 91.

[Adverts]

By 1970 Celtic had reached another European Cup final and Ernst Happel’s Feyenoord were looking to make their own history as the first Dutch club to lift the coveted crown. Danny McGrain remembered: “Kenny and I travelled as boot boys. We were there to watch how the boys prepared, watch the training, and see what was involved in training for the European Cup final. Being involved in the European Cup final at 20 was magnificent.”

There were seven of the Lisbon Lions playing that final. Davie Hay started and George Connelly replaced Bertie Auld on 77 minutes. Despite Tommy Gemmell giving Celtic the lead, the Bhoys lost 2-1 at the San Siro courtesy of Rinus Israel and the gifted Ove Kindvall. Willem Van Hanegem ran the show and Jimmy Johnstone was stifled with a double marking ploy.

It was mass disappointment after the euphoria of the “Battle of Britain” win over Leeds United in the semi finals. This was the catalyst for the introduction and emergence of new faces – the injection of fresh talent into the first team. The apprentices from the Barrowfield training ground, whose indoctrination into the Celtic Way had been gradual and methodical, found themselves in the spotlight. They became known as The Quality Street Gang and were arguably the most talented young footballers to come through the ranks at Celtic. Lou Macari remembers and attributes this to a toughness in Stein’s character and the good habits embedded in the European Cup winning side. “I’d be surprised if any of The Quality Street Gang didn’t all say the same thing. When we look back now, we owe our careers to the people who guided us.”

•Davie Hay – the “Quiet Assassin” – attended 18 year old Tony McBride’s wedding reception. McBride recalled: “I invited my friends from Celtic along in the evening. Davie Hay had scored a great goal against Rangers so he arrived a wee bit later. As the priest was saying his speech he noticed Davie coming into the reception hall and just stopped. No one else had seen Davie, and the priest just gestured over to him, and everybody stood up and gave him a huge round of applause.”

•In a testimonial game for Kilmarnock servant Frank Beattie, Kenny Dalglish scored six of Celtic’s seven goals. He became the new goalscoring sensation, and Stein gave him his debut against Hamilton in 1968 as a 17 year old. Ward White said: “I used to pick Kenny up every morning. Kenny, for a boy of 18, talked to a level above you in football. I never saw Kenny becoming a world-class player because he started off in right midfield and he was meant to be the next Bobby Murdoch. He got a couple of chances in the first team but he never really grabbed them. I don’t know why, we played Rangers and we beat them 4-1, 7-1 and I think 6-1 and Kenny scored about eight goals. Then we came down to Rugby Park, and I was in the pool that night for the Frank Beattie testimonial, and he scored six out there and you thought how did the boss know to play him at centre forward? And when he moved up there he became a world class player.”

Dalglish dismisses the comparisons to Murdoch early in his career. “Everybody’s themselves. For me, I was being played in midfield and then Jock pushed me up front after two or three years. Sometimes you’d get moved about as well to educate yourself and make you understand what people in a position other than you were playing would expect from you.”

•Though the likes of Dalglish, Hay, Macari and McGrain became household names. Others did not fare as well. George Connelly from the mining village of Fife was an exquisite prototype footballer. His brilliant close ball control, influence on a game and accomplished play led to Jock Stein comparing Connelly with the great Franz Beckenbauer during the 1974 World Cup. Connelly was earmarked as the natural heir to “Caesar” Billy McNeil.

Sadly, Connelly’s mental health suffered due to a disastrous failed marriage. This led to alcohol dependency and to Connelly’s subsequent retirement from the game at the tender age of just 26. David Cattanach firmly believes that the introduction of the big Fifer was the advent of a player who was to become, like many of the Lisbon Lions he had learned from, truly world class. “Without a shadow of a doubt I would say he was like Franz Beckenbauer. He had the same sort of ability to be able to go forward and play the ball and not just stay at the back. George arrived at Celtic as an old fashioned inside-forward. Jock Stein moved him to the back because George could ping a ball 40 or 50 yards right to your toe or he could play it five yards. It didn’t matter the distance. He was fantastic on the ball.”

•Vic Davidson was on the same wavelength as Dalglish but failed to reproduce his reserve team standards after stepping up to the first team. He was rated extremely highly by his team mate Ward White, who believes that at one stage there was not much to separate him from Kenny Dalglish. “Vic could dribble past four, five players, he could run with the ball. Obviously Vic didn’t reach the heights that Kenny Dalglish reached but I would say that Vic was the kingpin in the reserve team.”

•The brilliant Tony McBride was referred to as a pocket version of Jimmy Johnstone. As a youngster he was farmed out to Ashfield Juniors, where he linked up with Rangers protege Graham Fyfe to form a devastating partnership. McBride struck four in two games. Ashfield boss Louis Boyle raved: “The goal scoring of Fyfe and McBride has given a tremendous boost to our gates. They’re proving to be our biggest attraction since Stevie Chalmers.” But ill discipline in the Gorbals and poor lifestyle choices, coupled with an inability to stay on the right hand side of the law ensured his Celtic career never quite hit the high notes. Davie Hay said: “Tony was, at the time, one of the top youngsters of his age who was courted by a lot of teams down south. There were high hopes for him, the potential was there, but whatever happened didn’t materialise.”

•The gifted Brian McLaughlin was given his debut as a 16 year old in the 6-2 League Cup thrashing of Clydebank on 22nd September 1971. In 1973 his career was more or less ended by a horror tackle from Clyde’s Willie McVie. McLaughlin returned but was never the same player. Danny McGrain described it as the worst injury he’d seen on a pitch and has never forgiven McVie for this. Tragically, Brian McLaughlin was found dead in Aug 2009 in a canal in Falkirk.

•Pat McMahon enjoyed a meteoric rise from Kilsyth Rangers to sign for Celtic in 1967. A frustrating two seasons saw three first team appearances with two goals. McMahon joined Tommy Docherty in 1969 as Aston Villa pipped Dunfermline to his signature. In 1976 he moved to the NASL and now lives in the States.

•John Gorman was released after a single League Cup game. He was a good player but let’s not forget he was competing with Tommy Gemmell and Willie O’Neill.

[Adverts]

Davie Cattanach remembers how this young Celtic side, even without the promoted Davie Hay and George Connelly, would destroy all in their path. One fixture in particular that he remembered was the Reserve League Cup final of 1971. “We played Rangers and there was 25,000-30,000 at the game and it was the same at Ibrox, and we beat them 10-2 on aggregate – 6-1 at Ibrox and 4-1 at Celtic Park. That was us all just coming into it.”

It is fair to say that if this crop had stayed together they may very well have won a second European crown. After all, Celtic did reach the final again in 1970, the last eight in 1971, and semi finals in 1972 and 1974. This book is just another chapter in the rich history of Celtic Football. It’s a read for any football fan but supporters with Celtic ties would appreciate the content just a wee bit more.

•The Quality Street Gang by Paul John Dykes is published by Celtic, priced £19.99, and is available from club outlets and Amazon.

•The Quality Street Gang by Paul John Dykes is published by Celtic, priced £19.99, and is available from club outlets and Amazon.

•Follow Emdad on Twitter: @emdad07

[Adverts]

East London News A Force for the community…

East London News A Force for the community…